LH Bulletin andSurat Popular | Reports & Announcements | Mission Statement | How to Join the LH Listserv | Home

Part 1 (this part)

The Special Panels for Serious Crimes - Justice for East Timor?

Good East Timor-Indonesia Relations requires ending impunity

La’o Hamutuk investigated the work of the Serious Crimes Unit (SCU) in October 2001 (see La’o Hamutuk Bulletin Vol. 2, Nos. 6 & 7).UNTAET had been in place for almost two years, but the SCU had not accomplished very much and faced many challenges. The United Nations Security Council has extended SCU’s mandate until May 2005. Despite issuing indictments against senior Indonesian military figures the SCU has not been able to prosecute those most responsible for crimes against humanity or call important witnesses, as they reside in Indonesia. In addition, serious doubts remain about the quality of the judicial process of the Special Panels for Serious Crimes (SPSC).

Letter from NGO Forum to the UN Security Council: “We urge the UN not to leave East Timor alone with the consequences of crimes so terrible that they are characterized as against all humanity. It is time to take immediate steps to establish an International Tribunal for East Timor. This is the only mechanism that could address the current need for justice, the missing element so far, in the process of nation building for East Timor and worldwide respect for human dignity.” |

This article will assess the current process through evaluating the performance of the SCU, the Defense Lawyers Unit, the Special Panels and Appeals process to see if the system represents serious avenues for the people of East Timor to see justice for the crimes against humanity committed during the Indonesian occupation and after the referendum in 1999.

Background

Background

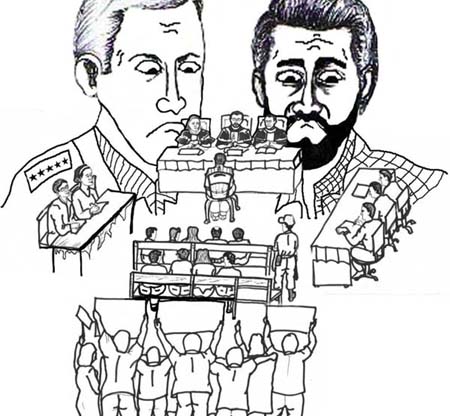

The United Nations established the SPSC in response to the huge numbers of horrific crimes committed by and under the direction of Indonesian military and political authorities in East Timor between 1975 and 1999, and due to the urgent need for justice that at the time (early 2000) was recognized by the East Timor people, the Indonesian government, and the international community. Both the UN International Commission of Inquiry in East Timor on 30th of January 2000, and the Investigative Commission into Human Rights Violations in East Timor (KPP HAM) found evidence of systematic and widespread crimes against humanity. Although they recommended establishing an international tribunal, the United Nations deferred to Indonesian promises to prosecute their own nationals through the Ad Hoc Tribunal in Jakarta.

The United Nations established the Special Panels for Serious Crimes to investigate and prosecute crimes against humanity in East Timor. The Special Panels for Serious Crimes comprises SCU, the Defense Lawyers Unit to the Special Panels (DLU), and the judges in the SPSC. In addition, the Court of Appeal hears appeals from the Special Panels and the ordinary courts. UNTAET regulations require one East Timor judge and two international judges to sit in the Special Panels and the Court of Appeal. The SCU consists entirely of international lawyers, although East Timor lawyers, police, forensic scientists, translators, and other investigators are undergoing training. The DLU is made up of international lawyers and is not currently training any Timorese lawyers.

The SPSC uses UNTAET regulations, Indonesian laws, and international human rights standards and have exclusive jurisdiction to try alleged perpetrators of crimes against humanity, including genocide, war crimes, torture, murder, and sexual offences. The definitions of these crimes are taken from wording of the 1995 Rome Statute which established the International Criminal Court. The SPSC represents the first instance of the new international laws being applied in actual cases.

What is happening now?

Although progress has been made in various areas, significant deficiencies continue to hamper the effectiveness and credibility of the serious crimes process.

The SCU has undergone significant downsizing since August 2003. UNPOL investigators fell from 23 to eight and UN investigators from 13 to 9 in December 2003. This affects the number and quality of investigations. For example, although the SCU asserted its jurisdiction in 89 cases which had applied for CAVR community reconciliation processes, blocking CAVR from handling these cases. None of these cases have been investigated. From May to July, SCU had no external liaison officer.

The trials at SPSCs have been progressing very slowly. Until mid-2003 only one panel was able to sit at a time as the UN were unable to recruit enough qualified international judges. The UN are currently looking for two more international judges and an East Timor judge to add to the existing English-speaking and Portuguese-speaking panels. Lack of communication between judges and lawyers has also caused scheduling problems.

The SCU estimates that less than half of the 1400 or so murders committed in 1999 will have been investigated. In addition, cases of torture, rape, and other crimes have also not yet been investigated.

Some of the problems of the Special Panels have improved recently. In addition to more material resources, Judge Phillip Rapoza says that judge turnovers are now handled to minimize disruption to the trials. Previously, the departure of international judges resulted in several cases needing to be started over and impeded the progress of many trials.

The DLU was created at the end of 2002, separate from the Ministry of Justice. Previously, there was only one public defender for serious crimes. The DLU currently consists of nine international lawyers, seven in Dili and one each in Baucau and Oecusse. Although cases still move slowly, mainly due to difficulties contacting witnesses and time taken traveling to districts, the DLU is much better resourced than it was. Though still lacking sufficient support staff, all lawyers have vehicles, adequate office space, and supplies.

The situation at the Court of Appeal is quite different. The Court was non-functioning until July 2003, as apparently neither the UN nor the government appointed judges. This resulted in an enormous backlog of cases especially since the Court hears appeals concerning both serious and ordinary crime cases. In addition, the Court of Appeal does not translate or transcribe its trials. Proceedings are conducted in English and/or Portuguese, and have never been recorded. Additionally, many defendants have been denied the right of appeal, raising serious questions as to whether the Court meets international standards.

SPSC Statistics Number of Indictments filed: 82 |

Capacity Building

One of the main purposes of the UN missions in East Timor is to transfer skills from international to local staff. International and East Timor judges on the SPSC stress the importance of training, and acknowledge that efforts towards capacity building needs to be increased.

The SPSCs are intended to support East Timor’s domestic capacity to try crimes against humanity. Sections of the Constitution provide for a judicial system which can prosecute such crimes.

It is clear that by May 2005, the national judicial system will not have the capacity to continue the serious crimes process. According to Nicholas Koumjian, Deputy General Prosecutor for Serious Crimes, the national staff of the SCU will not be prepared to continue investigations on their own. Koumjian says that the SCU itself is willing to train local staff, but the Ministry of Justice does not provide the SCU with enough people to train. There are similar problems in The Public Defenders Unit. Despite asking for East Timor trainees the DLU states that the Ministry of Justice has not assigned it enough trainee lawyers.

Limitations to the Serious Crimes Process

Trials at SPSC do not consistently meet minimum international standards. Perhaps most conspicuous is the ambiguity of procedural law during trials. International judges and lawyers come from a wide variety of backgrounds, including both common law and civil law disciplines. Procedural law varies greatly between these two disciplines, and even though there is a code of conduct that standardizes procedures for the Special Panels, judges do not follow it. The Special Panels follow UNTAET regulations, and if that is not sufficient, they turn to Indonesian law and international law, including jurisprudence from the international tribunals. As a result, there is significant inconsistency and confusion concerning procedure during trials. A lot of time is wasted at each trial deciding on what procedure to use, and depends on which judges are sitting on the panel. The Portuguese speaking panel tends to follow civil law procedures because the Portuguese-speaking countries use civil law, whereas the English speaking panel tends to favor common law procedures. In addition to slowing down trials, these procedural inconsistencies can result in unfair trials. There is the question of the legality of procedures being haphazardly decided while a trial is in progress as opposed to previously agreed upon. In addition, if defense lawyers are unclear on procedure, it can and has resulted in lower-quality defense for the accused.

As well as procedural law issues, codified law is ambiguous in East Timor, particularly with regard to criminal law. According to some public defenders, the civil law is incoherent; there has never been a systematic evaluation of UNTAET regulations in relation to Indonesian law. Indonesian law is not systematically applied, as illustrated in the case of Armando dos Santos, which went to the Court of Appeal. Dos Santos was charged and convicted under an UNTAET regulation, but on Appeal judges decided that UNTAET regulations could not be applied to acts committed before they went into effect (in 2000), and that the underlying law was Portuguese (not Indonesian, as everyone else understood). This caused a huge controversy concerning which law should be applied in East Timor. The Indonesian/Portuguese issue was later clarified by an act of parliament. At the time it had been strongly inferred that the two Portuguese Appeals Court Judges were acting contrary to due process. Parliament subsequently reaffirmed that Indonesian Law should be used in cases where there are no UNTAET Regulations. According to the observations of the Judicial System Monitoring Program, the ambiguity of civil law in East Timor is not a large concern in cases of serious crimes because international law is overwhelmingly used and applicable.

Another concern is the inequality between prosecution and defense. The prosecution, under the SCU, has much more funding and support than the DLU. The DLU has no quality control mechanism or standards of practice. Although the quality of defense has improved significantly since the creation of the DLU, not all of the public defenders in the DLU have sufficient experience in criminal trials and international human rights law. It is a concern that there are no laws or standards concerning the practice of law in East Timor, except for a restriction on Indonesian nationals practicing in the country. This lack of regulation, combined with too few lawyers with too little practical experience, inevitably results in some defendants receiving poor representation in both ordinary and serious crimes.

Another concern is the inequality between prosecution and defense. The prosecution, under the SCU, has much more funding and support than the DLU. The DLU has no quality control mechanism or standards of practice. Although the quality of defense has improved significantly since the creation of the DLU, not all of the public defenders in the DLU have sufficient experience in criminal trials and international human rights law. It is a concern that there are no laws or standards concerning the practice of law in East Timor, except for a restriction on Indonesian nationals practicing in the country. This lack of regulation, combined with too few lawyers with too little practical experience, inevitably results in some defendants receiving poor representation in both ordinary and serious crimes.

On some occasions, busy trial schedules have forced assistant defense lawyers to represent suspects in court. The limited number of support staff can make it difficult for lawyers to find witnesses. Furthermore, many witnesses are in West Timor and refuse to come to East Timor. The courts require witnesses to come in person.

These difficulties, compounded by confusion about the laws and procedures they are to use, have caused some public defenders to express their frustration from not being able to represent their clients as well as they should. They also feel that, considering the disparity in funding, the DLU is a priority for the serious crimes process.

Problems of poor administration and court management in the SPSC have lessened since the early days. However, problems which remain make it hard for trials to run smoothly and in a timely manner. There is also a concern that international and national Special Panels judges, along with serious crimes prosecutors and defenders, may not have sufficient experience in the relevant fields of criminal law, international law, including international humanitarian and human rights law.

Furthermore, poor and insufficient translation remains a major issue. Proceedings are conducted in at least four languages (Portuguese, English, Bahasa Indonesia, and Tetum), and frequently other local languages as well. Translation is not always available in all necessary languages, and there remains a shortage of professionally trained translators. Language barriers affect public awareness of court proceedings and the rights of the accused to interpretation. The method of consecutive translation currently used inevitably causes miscommunication and is time consuming. Courts have equipment enabling simultaneous translation (using earphones) that hasn’t been used. The Special Panels has requested four simultaneous translators

The detention practices of the Special Panels are yet another serious issue. All suspects have the right to prompt judicial review of their detention and the right to a trial without delay. According to international standards, "pre-trial detention should be an exception and as short as possible". However, in many cases, the accused are being detained for prolonged periods of time, in some cases for years. Under the Transitional Rules of Criminal Procedure, detention of suspects should be reviewed by a judge every 30 days. Yet, at any given time over the last year, it was usual for between one third and one half of all detainees held in Becora prison to be held on detention orders that had expired. There is significant concern over the inadequate judicial review of detentions, as well as the maltreatment of detainees while in police custody or prison.

The court’s most serious limitation is the non-cooperation of Indonesia with the serious crimes process. Since the majority of those indicted have been given sanctuary by Indonesia, the only ones being prosecuted for crimes against humanity are low-level East Timor former militia or TNI. Many of them are uneducated and illiterate, and many of them were coerced into joining the pro-integration militias.

Indonesia says that they will defy the SCU indictments because they claim that the UN has no mandate to try Indonesian citizens in East Timor. In August the Indonesian Government announced that it would refuse to cooperate with a UN Commission of Experts’ assessment of the Ad Hoc Tribunal and SPSC recently proposed by the Secretary General. Indonesia will not agree to any kind of legal cooperation with the process in East Timor unless they feel significant pressure to do so. However, it seems that all the major players in the serious crimes process are simultaneously skirting the responsibility of dealing with Indonesia.

The Special Panels for Serious Crimes is supposedly a hybrid national and international system. Although the UN provides funding and hires international staff, authority is officially with the Ministry of Justice and the Dili District Court (except the DLU). To be effective outside of East Timor arrest warrants issued by the SCU have to be forwarded to Interpol by the East Timor General Prosecutor. Consequently, East Timor incurs the political costs of prosecuting high level Indonesian nationals.

Prosecutor General Longuinhos Monteiro told La’o Hamutuk that it is the responsibility of the East Timor Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation to pressure Indonesia, so that the burden does not all fall on his shoulders. However, the government has been reluctant to jeopardize their fragile relationship with Indonesia, and has distanced itself from the process. President Gusmao has been very vocal in his disagreement with the SCU indictments of top Indonesian military figures citing the importance of good relations with Indonesia. According to SRSG Hasegawa, it is the responsibility of the UN member states to push for Indonesian cooperation.

Future of the Serious Crimes Process

The Security Council has approved funding for the serious crimes process until May 2005. However, funding is not likely to be available beyond that date. Once the UN leaves East Timor, along with all of its resources, the justice system that is left will not have the capacity to investigate or prosecute serious crimes. Cases could be transferred to the Ministry of Justice, or perhaps to an alternative justice system, such as an international tribunal.

The Security Council has approved funding for the serious crimes process until May 2005. However, funding is not likely to be available beyond that date. Once the UN leaves East Timor, along with all of its resources, the justice system that is left will not have the capacity to investigate or prosecute serious crimes. Cases could be transferred to the Ministry of Justice, or perhaps to an alternative justice system, such as an international tribunal.

Moreover, it is unclear what will happen to the cases from crimes that occurred prior to 1999. After all, only about 1% of the killings during the Indonesian occupation occurred in 1999. General Prosecutor Monteiro admits that the current justice system in East Timor is unable to handle pre-1999 cases. "Institutional enhancements", it is said, will have to be made if they are to tackle those cases.

Although the logistics of investigating and prosecuting pre-1999 cases will be difficult and complicated, it is the collective will of the people of East Timor that justice be carried out for crimes that were committed during the entire occupation. It is essential to the reconciliation process that these war crimes and criminals are not ignored as if they had never happened. Unfortunately, a lack of East Timor and international political will to prosecute these criminals has created a "black hole" of cases that may never be investigated, much less prosecuted.

It is clear that the serious crimes process in its current form has not and will not bring about justice for the people of East Timor. In addition to the many limitations and deficiencies of the process that prevent it from meeting international standards, there is also a severe lack of capacity building that has taken place thus far.

Another hope for justice Durvalina Belo Magno, usually known as Durva, 35, mother of five children is one of the thousands of victims of the 1999 post referendum violence. She watched as her husband was abducted by the AiTarak militia in September 1999. She never saw him again. This is how she feels about the United Nations and the Serious Crimes Unit (SCU). “The SCU do not provide justice for the families of the victims. Look around us and you can see the militia are still free, getting work and enjoying independence,’’ She said in tears. “Our lives are nothing if the Indonesian and East Timorese perpetrators of crimes against humanity are still free in Indonesia and not tried according to international law. We need real actions from the SCU and the international community. We need to get at the roots of evil and not just cut the branches.” Durva, a member of the Timor Leste National Alliance for an International Tribunal, had much hope for the SCU in the beginning, which she has now lost. “We still hope for justice through the establishment of an International Tribunal.” She and other victims will continue to struggle for justice. “Maybe we won’t achieve justice today, but maybe in the future we will find peace in our lives and for our husbands, younger siblings, older siblings, children and friends we have lost.” |

Allegedly guilty of crimes against humanity | |||

| Named by KPP HAM, the Indonesian Human Rights Commission | Named by Geoffrey Robinson ‘East Timor 1999 Crimes against Humanity’ commissioned by Office of High Commission for Human Rights (only Indonesian officers above the rank of Lt. Col included) | Tried by the Human Rights Ad Hoc Tribunal in Jakarta, Indonesia | Indicted by the The Special Panels for Serious Crimes, East Timor

|

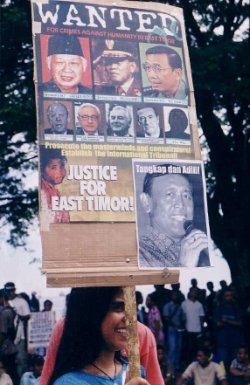

General Wiranto Maj. Gen Adam Damiri Maj. Gen Zacky A Makarim Maj. Gen H R. Garnadi Lt. Gen Johny Lumintang Col. (Inf) FX Tono Suratman Col. (Inf) M Noer Muis Col. (Pol) Timbul Silaen Col. (Inf) Herman Sedyono Lt. Col (Inf) Yayat Sudrajad Lt. Col Burhanudin Siagian Lt. Col (Inf) Sudrajat A.S. Lt. Col (Inf) Jacob Joko Sarosa Lt. Col (Inf) Asep Kuswandi Lt. Col (Inf) Ahmad Masagus Maj. (Inf) Yakraman Y Agus Capt. (Inf) Tatang Abilio Soares Dominggos Soares Guelherme dos Santos Edmundo Conceicao de Silva Suprapto Tarman | General Wiranto Maj. Gen Adam Damiri Maj. Gen Zacky A Makarim Maj. Gen Kiki Syahnakri Maj. Gen Endriartono Sutarto Maj. Gen Sjafrie Sjamsuddin Maj. Gen Tyasno Sudarto Maj. Gen Syahrir Brig. Gen Arifuddin Brig. Gen Mahidin Simbolon Gen. Subagyo Hadisiswoyo Lt. Gen Sugiono Lt. Gen Djamari Chaniago Col. (Inf) FX Tono Suratman Col. (Inf) Noer Muis Col. Mudjiono Col. Sunarko Lt. Col (Inf) Yayat Sudrajad | Maj. Gen Adam Damiri Col. (Inf) FX Tono Suratman Col. (Inf) Noer Muis Col. (Pol) Timbul Silaen Col. Herman Sedyono Lt. Col (Inf) Yayat Sudrajad Lt. Col Liliek Koeshadianto Lt. Col Asep Kuswani Lt. Col Endar Priyanto Lt. Col Soejarwo Lt. Col (Pol) Adios Salova Lt. Col (Pol) Hulman Gultom Gatot Subyakto Ahmad Syamsudin Soegito Eurico Guterres [the only conviction not yet overturned] Abilio Soares Leonito Martins | General Wiranto Maj. Gen Adam Damiri Maj. Gen Zacky A Makarim Maj. Gen Kiki Syahnakri Col. (Inf) FX Tono Suratman Col. (Inf) Noer Muis Lt. Col (Inf) Yayat Sudrajad Abilio Soares |

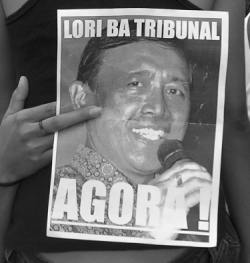

Safe Haven for Wiranto Currently, the biggest controversy surrounding the Serious Crimes Unit is the indictment filed in February 2003 against General Wiranto and six other senior Indonesian military officials on 10th of May 2004. Afterwards the US Government put Wiranto on its visa watch list. The RDTL General Prosecutor is responsible for forwarding this warrant to Interpol for worldwide distribution, but he has so far refused to do so. If he did, Wiranto would risk arrest if he left Indonesia. The efforts of the SCU to bring Wiranto to justice are commendable. However, the process is significantly limited by the SCU’s pending closure in May 2005 as well as the Indonesian government’s refusal to cooperate, and criticisms from East Timorese leaders. East Timorese leaders have distanced themselves from the indictment saying it is important for the economy and security to have good relations with Indonesia. President Xanana Gusmao, Ramos Horta and other East Timorese leaders have negotiated directly with Wiranto and his defense lawyers to discuss the serious crimes process without the approval of Parliament and other government institutions. Several times East Timorese leaders have spoken and acted against an international tribunal contrary to the demands of survivors and civil society. This interference in the judicial process is contrary to the RDTL constitution. Strong support from the international community and links between Indonesian and East Timorese are the only way to put pressure on a new Indonesian government to prosecute the masterminds of gross human rights violations and ending impunity in both countries. The General Prosecutor should follow due process and issue the arrest warrants against Wiranto, Yayat Sudrajat and other perpetrators. The arrest and trial of Wiranto and the other Indonesian perpetrators is the only way to justice and reparation not only for East Timorese but also to remind human rights violators everywhere that they are not free or immune from prosecution. |

Good relations between East Timor and Indonesia have been cited as the principle reason for the East Timor Government not to try to indict Indonesian Military Generals. La’o Hamutuk, as an East Timor non-governmental organization advocating justice for all East Timor people and victims of crimes against humanity everywhere, believes that good relations between the two countries requires giving support to Indonesian demands to end impunity and support the democratization process in Indonesia, as well as the right to justice and reparations for victims of gross human rights violations in both countries. La’o Hamutuk further supports the establishment of a UN Commission of Experts to evaluate the work of the Serious Crimes Unit, the Special Panels, and the Ad Hoc Human Rights Tribunal in Jakarta, and finally recommends that the Commission should push for the establishment of an International Tribunal.

On 16th August, Foreign Minister José Ramos-Horta and Indonesian Foreign Minister Hassan Wirayuda said that in the interest of maintaining good relations between the two countries, the Republic of Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of East Timor would agree not to bring the crimes committed in East Timor in 1999 before an international tribunal nor to lobby the UN to establish an international tribunal (Timor Post and Suara Timor Lorosa’e reports 17th August).

The Ambassador of East Timor to Indonesia Arlindo Marcal said that in the meeting of the two Foreign Ministers in Bali on 15 August, neither supported the wishes of UN Secretary General Kofi Annan to create a UN Commission of Experts, predicting that having a Commission conducting studies and investigating cases would have many negative effects. Arlindo Marcal also supported Ramos-Horta’s opposition to trying human rights violations committed in East Timor in an international tribunal. Opposition to the creation of an international tribunal or a UN Commission of Experts is supposedly based on the two neighboring countries wanting to retain good relations. President Xanana Gusmão has supported this position. Meanwhile Prime Minister Mari Alkatiri has stated the Government does not yet have a formal position on the establishment of a UN Commission of Experts and International Tribunal.

Recently the East Timor National Alliance for an International Tribunal refused an idea proposed by the Foreign Minister two years ago to establish an international truth commission, which was supported by the U.S. Government; and a proposal to extend the mandates of the Timorese Commission of Reception, Truth and Reconciliation to handle the rest of the serious crimes cases through community reconciliation.

The slow progress of the SCU and Special Panel as well as the failure of the Ad Hoc Human Rights Tribunal in Jakarta to fulfill international law have prompted the UN Secretary General to establish a UN Commission of Experts. The Secretary General has called on the international community to exercise its responsibility to set up a new judicial process that would bring justice for victims. The European Commission, New Zealand Government, international human rights defenders and East Timor civil society have supported the establishment of a UN Commission of Experts.

La’o Hamutuk, as a member of the National Alliance for an International Tribunal states that all victims of crimes against humanity committed in East Timor have a right to justice and the right to reparations through a free and fair legal system under the auspices of the international community.

The crimes committed in East Timor are an international responsibility and as such, the entire international community is responsible for ending the immunity from prosecution enjoyed by the perpetrators of crimes against humanity. The UN created the Serious Crimes Unit and the Special Panels which has the legal jurisdiction, but not the practical power to arrest perpetrators outside East Timor. The Serious Crimes Unit and the Special Panels have tried East Timor citizens who are not ultimately responsible for the crimes against humanity committed in East Timor, though this is better than no process at all.

We believe that the UN plan to end the Serious Crimes Unit’s investigations in November 2004 and trials of serious crimes before the Special Panels in May 2005 will have serious consequences in that cases will be left unfinished. One idea in relation to this arrangement is that the Special Panels should end, since it is only trying East Timor defendants; they could be tried in the Dili court system though this suffers from lack of resources and capacity. On the other hand, taking such a decision would mean abandoning international responsibility and would leave the East Timor people alone with the responsibility to pursue justice.

Prosecution through a fair and impartial international tribunal should be prioritized by the international community, with the support of the government of East Timor. Trying those responsible for the crimes against humanity committed in East Timor will lay strong foundations on which other countries can build - especially Indonesia - to end impunity and prevent military abuses against civilians.

The relationship between East Timor and Indonesia cannot be built solely on economic grounds. East Timor as a small nation needs the protection of the law and the international community to ensure an equitable redress of grievances against a much more powerful neighbor which has invaded and destabilized them in the past.

In addition to committing numerous crimes against humanity during 24 years of illegal occupation of East Timor, Indonesia has a long and dark history of gross human rights violations. Examples include the pogroms against members of the Indonesian Communist Party and its supporters in 1948 and 1965, abductions and forced disappearances of democracy and human rights activists during the Suharto dictatorship, ongoing military operations in Aceh and West Papua, the Haur Koneng massacre in Lampung, and the Universitas Tri Sakti students, murdered shortly before the downfall of Suharto.

Indonesian civil society, in their struggle for a return to democracy and the rule of law, is demanding that crimes from Suharto’s New Order regime be brought to trial. This is the only way to break the chains of war criminals’ immunity from prosecution. The people of East Timor, as members of the international community, have a responsibility and duty to ensure that this is carried through. By extension, good relations between East Timor and Indonesia must be based on respect for universal human rights as supported by instruments of international law and Section 10 of East Timor’s constitution:

Indonesian civil society, in their struggle for a return to democracy and the rule of law, is demanding that crimes from Suharto’s New Order regime be brought to trial. This is the only way to break the chains of war criminals’ immunity from prosecution. The people of East Timor, as members of the international community, have a responsibility and duty to ensure that this is carried through. By extension, good relations between East Timor and Indonesia must be based on respect for universal human rights as supported by instruments of international law and Section 10 of East Timor’s constitution:

The Democratic Republic of East Timor shall extend its solidarity to the struggle of all peoples for national liberation.

The Democratic Republic of East Timor shall grant political asylum, in accordance with the law, to foreigners persecuted as a result of their struggle for national and social liberation, defense of human rights, democracy and peace.

The procedures enacted in the Jakarta Ad-Hoc Human Rights Tribunal and convictions have failed to meet international standards. The Tribunal has demonstrated that the military enjoy institutionalized immunity from prosecution. The generals’ involvement in crimes against humanity were presented merely as crimes by omission, since they were 'unable to prevent' their inferiors from committing the crimes. The Jakarta Ad-Hoc Tribunal has not fulfilled the principals of state and individual responsibility in bringing to justice perpetrators of crimes against humanity.

In conclusion, we call for:

International pressure to build the political will to establish an international tribunal and support the creation of a Commission of Experts.

The Government of East Timor to fully support the demands of the victims of crimes against humanity to respect their right to justice, right to know and right to reparations through a free and fair legal system.

Strong support from the RDTL government to establish an international tribunal and support for a UN Commission of Experts to evaluate the work of the Serious Crimes Unit and the failures of the Jakarta Ad-Hoc Tribunal. This follows international wishes to bring to justice perpetrators of crimes against humanity, especially in East Timor, Indonesia as well as other countries.

We will no longer hear his strong criticisms of militarism, impunity of high military officials, and state violence in Indonesia. His figure will no longer accompany the families and victims of forced disappearances, mass murder and military violence which accompanied the civilian demand for the arrest and trial of Wiranto in front of the Presidential Palace and the TNI Headquarters. Munir, 38, who was fondly called 'Cak' Munir died above Hungary, two hours before his plane landed at Schipol Airport, Holland. At the time of writing Cak Munir’s official cause of death has not been established. [After this Bulletin went to press, Dutch autopsy results indicated that he had been poisoned with arsenic.] He had been planning to continue his doctorate studies in International Human Rights Protection at Utrecht University.

We will no longer hear his strong criticisms of militarism, impunity of high military officials, and state violence in Indonesia. His figure will no longer accompany the families and victims of forced disappearances, mass murder and military violence which accompanied the civilian demand for the arrest and trial of Wiranto in front of the Presidential Palace and the TNI Headquarters. Munir, 38, who was fondly called 'Cak' Munir died above Hungary, two hours before his plane landed at Schipol Airport, Holland. At the time of writing Cak Munir’s official cause of death has not been established. [After this Bulletin went to press, Dutch autopsy results indicated that he had been poisoned with arsenic.] He had been planning to continue his doctorate studies in International Human Rights Protection at Utrecht University.

Cak Munir was a representative of the Indonesian Legal Aid Foundation, a founding member of KontraS (Commission for Missing People and Victims of Violence) and the Independent Journalist Alliance. He was also part of 12 other non-government organizations and an advocate for the victims of 1998. The struggle of the victims was inspired by his mother, a struggler for the Women’s Group Madres Plaza de Mayo in Argentina, and his experiences when saving those who were forcibly disappeared in 1998. As the KontraS Coordinator, he was also involved in helping and organizing those most closely affected by the mass murder directed by army factions loyal to Suharto in 1965; the massacre at Tanjung Priok in 1984; the Trisakti 1-11 student murders in 1997, as well as many cases in Aceh and West Papua; and numerous disappearances throughout the New Order period.

KontraS was first to uncover evidence of Kopassus involvement in the infamous 1998 disappearances cases. His bravery at stating the facts openly concerning military involvement in the case shook high-ranking military officials. He also did this when he became a member of the Human Rights Commission to East Timor in 1999. In 2003, he strongly opposed the Military Emergency Operation in Aceh and succeeded in disclosing a number of facts regarding Kopassus involvement in the murder of Theys Eluay, the West Papuan Independence Movement Leader.

Cak Munir completed his Bachelor Degree at the Law Faculty, Brawijaya University, Malang, East Java. He was active in the Islamic Students Association (HMI) and chosen to lead the Law Faculty Student Senate of Brawijaya University, 1987-1988. His anti-militarism started to become evident when he opposed the Student Regiment (Menwa) activities in the compound of Brawijaya University.

Beginnings in the Labor Movement

On completing his bachelor degree, Cak Munir provided his services to the Legal Aid Institute (LBH) Surabaya Pos Malang from 1989-1993. An admirer of Salvador Allende, Cak Munir began to be active in coordinating the Lawang, Pasuruan and Malang laborers in the 1990s. He and approximately 200 laborers won a civil claim case against the plastic factory PT Sido Bangun. This was the beginning of his shining career and LBH Surabaya appointed him as the Labor Division Coordinator. Every night he held discussions with labor groups of the Tandes, Rungkut, Sidoarjo, and Gresik areas at the office or at laborers’ boarding houses.

The Marsinah female laborer murder case in 1993, made him aware of military involvement in labor cases. After the Marsinah case, together with the Solidarity Committee for Marsinah (KSUM) Cak Munir started the Anti-Military Involvement Campaign in labor conflicts. He became the defense lawyer for 22 laborers of PT Maspion, Sidoarjo in East Java, who had been accused of destroying company assets and illegally going on strike. Cak Munir himself was found 'guilty' of meeting with his clients at the Pos Malang LBH Office and was instructed to report to the Sector Police Station in Blimbing, Malang. However, he refused to carry out the order of the Malang District Court.

Cak Munir did not limit his work time and activities just to labor. He was a lawyer and paralegal facilitator. He was a friend and helper in a number of cases including the shooting of citizens opposing the building of a reservoir in Nipah, Bangkalan, Madura; the farmers case in Jenggawah, Jember; the community opposition to the construction of high voltage power lines in Singosari, Gresik. He brought legal claims against 48 companies in Surabaya River. He helped RENETIL colleagues like Jose 'Samalanrua' Neves in Surabaya and Malang. He helped East Timor colleagues who were running from arrest after trying to jump into the Dutch and Russian Embassies in Jakarta.

Spreading Wings

In 1995 after becoming the Operational Head of LBH Surabaya, the Indonesian Legal Aid Foundation (YLBHI) invited him to become the Interim Director of LBH Semarang, Central Java for three months. Not long after, YLBHI appointed him as the Operational Head, located in Jakarta and entrusted him with the position of KontraS Coordinator. KontraS was established in Dili in 1999 and also in Aceh. He was hospitalized and operated on after his hand was stamped on by a soldier when the army entered the YLBHI office at the time of the PDI-P headquarters attack on 27 July 1996.

The failure to democratize the YLBHI internally disappointed him and he resigned from the organization that he was so proud of and established Imparsial, an Indonesian human rights monitoring group in 2002. He continued to give time to KontraS and he was still involved in organizing the victims of serious human rights violations even though his health started to deteriorate.

He helped establish a number of organizations to fight against the impunity of military officials and to enforce human rights. With his wit and commitment, he was on the Advisory Board of IKOHI (Indonesian Families of Missing Persons’ Organization) and alternative radio programs Voice of Human Rights, Voice of the Voiceless. Although he was willing to be on the Advisory Board for the Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation (CAVR) in East Timor, together with other Human Rights Organizations and victims, he rejected the establishment of the Indonesian Truth and Reconciliation Commission. This contradicted decisions taken by a number of other non-government organizations who he had worked with.

For his dedication, a number of national and international institutions have bestowed honors on him. These include Man of the Year by Moslem UMMAT Magazine, One of 20 Young Asian Leaders for the New Millennium by Asia Week, Yap Thiam Hien Human Rights award for KontraS, UNESCO, the Right Livelihood Award an Alternative Nobel Prize, by the Swedish Government, and the 'Figure of Youth Revolution' by Gatra Magazine.

Prayers have been sent since news of his death was received by KontraS staff on Tuesday 7th of September. His short life provided inspiration and energy to the pro-democracy movement and Human Rights in Indonesia and internationally. Rest in peace, comrade!

| Munir (right) and family of missing persons on the anniversary of International Human Rights Day, December 2003. |

We are looking both East Timorese and international activists to join our staff collective.

National Researcher

International Researcher

Each staff member at La’o Hamutuk works collaboratively with other staff to research and report on the activities of international institutions and foreign governments operating in East Timor. Staff members share responsibilities for administrative and program work, including our Bulletin and Surat Popular publications, radio programs, public meetings, advocacy, popular education, coalitions with other East Timor organizations, and exchanges with people in other countries. Each staff member is responsible for coordinating at least one of La’o Hamutuk’s main activities.

Requirements

· Activist background, experience and orientation

· Strong commitment to making the development process in East Timor more democratic and transparent

· Commitment to share skills and help build other staffers’ capacity

· Responsible, with a strong work ethic and willingness to work cooperatively and creatively in a multi-cultural setting

· Understanding of and willingness to work against gender discrimination

· Strong written and verbal communication skills

· Ability to present factual information from investigative reporting

· Sound physical and psychological health

· Experience in one of the areas cited above

· Work experience in international development, policy research, and/or international solidarity desirable

Additional requirements for internationals

· Fluency in written and spoken English (native speaker preferred)

· Strong organizational and computer skills

· Knowledge of East Timor’s history and politics

· Experience living and working in a developing country; interest and capacity to live simply

· Fluency in or willingness to learn Tetum

· Indonesian and/or Portuguese language skills desirable

Additional requirements for East Timorese

· Fluent Tetum and Bahasa Indonesia, and ability to write and translate between these languages

· Basic organizational and computer skills, and willingness to expand those skills

· Investigating skills, with the ability to write factually and clearly, desirable

· English and/or Portuguese language skills desirable.

To apply, please bring the following documents to our office in Farol (next to Perkumpulan HAK and the Sah'e Institute for Liberation) or email them to laohamutuk@easttimor.minihub.org

Cover letter explaining your reasons for wanting to work with La’o Hamutuk

Curriculum vitae (CV)

Two professional references from previous employers or organizations

Writing sample about the development process (one or more pages)..

Applications will be considered as we receive them.

La’o Hamutuk, The East Timor Institute for Reconstruction Monitoring and Analysis

P.O. Box 340, Dili, Timor-Leste

Mobile: +670-7234330; Land phone: +670-3325013

Email: laohamutuk@easttimor.minihub.org; Web: http://www.laohamutuk.org