LH Bulletin andSurat Popular | Reports & Announcements | Mission Statement | How to Join the LH Listserv | Home

Part 1

The Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation (CAVR), although temporary, is one of East Timor’s largest institutions. Many people hope that CAVR, together with the formal justice system, can play a critical role in the transition of East Timor from war to peace, from foreign occupation to independent democracy. Although all the commissioners are East Timorese, many key staff, all funding, and the basic structure and methodology come from overseas. CAVR is trying to establish the truth about events from 1974 to 1999, to negotiate reconciliation agreements between victims and perpetrators of minor crimes, and to provide a mechanism to recognize and appreciate the suffering of the victims during the 1975 civil war and subsequent Indonesian occupation of East Timor. CAVR is most of the way through its work, and plans to finish by October 2004.

La’o Hamutuk’s mandate is to report on international institutions, and the CAVR is primarily East Timorese, with East Timorese commissioners and more than 90% East Timorese staff. However, it has relied heavily on international consultants, advisors, and leadership. Furthermore, CAVR is funded by international donors, and its work relates to crimes committed here by Indonesian forces with broader international support. As we have said before, justice for crimes against humanity committed in East Timor remains an international responsibility. This article explores the structure, work and mandate of CAVR, as well as some decisions and controversies which it has to deal with. La’o Hamutuk

CAVR was established by UNTAET Regulation No. 10/2001, issued on 13 July 2001. CAVR has three areas of activity, with the objective of promoting human rights in East Timor. CAVR was originally to operate for two years, and has been extended for an additional six months. When CAVR finishes its work during 2004, it will make recommendations to the government. One possible recommendation, which La’o Hamutuk would support, would be the creation of a system of alternative dispute resolution for minor crimes and grievances, perhaps similar to the community reconciliation processes used by CAVR.

The mandate of CAVR includes

The idea to establish CAVR was discussed in the CNRT Congress in 2000, and at that time, the commission was known as the Commission for Acceptance and Reconciliation. The United Nations had already been discussing a truth and reconciliation commission for East Timor, and the U.N. was heavily involved from the beginning, bringing in consultations from the International Center for Transitional Justice and elsewhere. The CNRT workshop included participants from Association of Former Political Prisoners (ASEPOL), ET-WAVE, FOKUPERS, Yayasan HAK, PAS-Justice, UNHCR, UNTAET Legal Affairs, UNTAET Human Rights Unit and CNRT.

According to Jacinto Alves, one of the national commissioners, CAVR is important because it will help solve the problem of minor violations, via the process of community reconciliation. The courts alone do not have the capacity to deal with all the minor violations, and if there were no CAVR these cases might never be resolved.

Truth commissions have become a popular recipe for reconciliation in several post-conflict societies; East Timor’s CAVR is the 21st of its kind. In July, CAVR staff and a Commissioner participated in a conference in Peru, exchanging experiences with commissions from Peru, Sierra Leone and Ghana, to help improve the management of CAVR in East Timor.

Many of the commissions elsewhere have had mixed results, often because perpetrators didn’t fully cooperate, or because findings were uncomfortable for government officials who then suppressed their reports or refused to implement their recommendations. In some countries, commissioners or staff have been brutalized or terrorized in an effort to prevent the commission from doing its work. East Timor’s CAVR, fortunately, has suffered no such intimidation, and we remain hopeful that its work will be completed successfully, and its findings widely publicized and followed.

Most of the international advisors and consultants involved in establishing East Timor’s CAVR have had little experience with other countries’ commissions. Some of those who have, worked with South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). But every country’s situation is unique, and South Africa’s differs from East Timor’s in several ways:

The establishment of CAVR in East Timor is based upon the assumption that making the truth known to everyone, regarding who did what to whom in terms of serious human rights violations, can be a basis for long-term reconciliation in a society that is recovering from war and widespread serious human rights abuses.

One of the most important functions of the truth commission is to investigate past human rights violations and to write a detailed report that presents and explains not only individual violations, but also the patterns and policies that underlay those violations. The report will be primarily based on victims’ testimonies and research conducted in East Timor, supplemented by some research in other countries. Although CAVR is trying to gather information from Indonesian military and government offices, there has been very little cooperation. Although the report will be useful, it will not be a complete truth, as the commission has no access to information or viewpoints held only by the commanders or major perpetrators.

In addition to this report, CAVR tries to promote and facilitate apologies to the victims _ both individually, person-to-person, as well as to whole communities _ by the perpetrators of brutality. In this way, they are implementing restorative justice and helping to make it possible for former enemies to live peacefully side-by-side.

The Structure and Work Processes of the CAVR

The highest decision-making mechanism, for issues of a political nature, are the seven national commissioners Aniceto Guterres Lopes (Chair), Father Jovito de Araújo (Deputy-Chair), Jacinto Alves (Truth-Seeking), Ms Olandina Caeiro (Treasurer), Ms Isabel Guterres (Reception/Victim Support), José Estêvão Soares (Truth-Seeking), and Rev Agustinho de Vasconselos (Reconciliation). Some of the commissioners work full-time for CAVR, and some are part-time. Each commissioner is also responsible for CAVR activities in two districts, so they often have to travel outside of Dili.

For the Commission to make a decision, five of the seven commissioners must be present. Several commissioners have admitted that in certain matters they are only asked to handle important political policies, making it difficult for them to know about program implementation. However, some CAVR staff feel that some commissioners should be more pro-active regarding finding out about implementation in the field. Some local CAVR staff also told us that the national commissioners are often late in approving salary increases, and are slow in making decisions regarding public hearings.

The implementation of decisions and coordination of activities in the field is handled by the Senior Management Team (SMT), which consists of the coordinators of each division, executive director Lucio dos Santos and program manager Galuh Wandita.

Community Reconciliation Division (CRP)

Via this division, CAVR promotes reconciliation within communities, by “promoting acceptance and re-integration of those people that have caused suffering to their communities” by committing non-serious crimes such as theft, minor attacks, burning and killing of livestock. This makes the perpetrators of these kinds of crimes accountable to the victims, as a form of restorative justice. CAVR implements this through the CRP, by finding out whether the perpetrator wants to make reparations by doing something meaningful for the victim and the community. For example, a crime of burning a house can be solved by asking the perpetrator to rebuild the house. “Community Reconciliation Agreements” are registered at the district court as a guarantee that the reconciliation process will be implemented, that the punishment is in accordance or on the same scale as the crime committed, and that it does not violate human rights. CAVR is responsible to refer serious crimes (such as murder, rape, large scale destruction and planning to carry out such crimes) to the General Prosecutor for handling via the court process.

The SCU (Serious Crimes Unit) checks the deponent statements that are received by CAVR against its files of suspects who are believed to have been involved in serious crimes in 1999. By late October, CAVR had sent 1115 deponent statements to the SCU, which has exercised its exclusive jurisdiction in 69 cases. The SCU would not tell La’o Hamutuk if any of these alleged perpetrators of serious crimes have been indicted or are being pursued actively, but only that all these cases are “under investigation.”

For minor crimes, CRP makes efforts to bring the perpetrator to a reconciliation agreement with the victims and/or the community. By mid-October 2003, the CRP division had received requests for CRPs from more than 1,100 perpetrators of minor crimes. Of these, 454 have participated in 82 hearings, 89% of which have resulted in community reconciliation agreements. All the CRP processes are entered into the CAVR database as documentation. Although this is an impressive number of cases in a short time, it is a small fraction of the minor political crimes committed in East Timor. In the last month of Indonesia’s quarter century of occupation, for example, TNI and militia burned tens of thousands of buildings, and forced hundreds of thousands of people to flee.

In principle, people give testimony on a voluntary basis, although one of the incentives for perpetrators to come forward is that entering a CRP agreement guarantees immunity from prosecution for the minor crimes which are the subject of the agreement. However, some victims do not want to give testimony, because they feel that they have no legal security. This situation occurs because victims and perpetrators know that CAVR can refer information that it obtains to the courts, which could prosecute if the case is classified as a serious crime. Former pro-autonomy supporters also often feel frightened to give testimony because they feel that this will only re-open old wounds, and that this is dangerous for them in the middle of a community that is pro-independence. La’o Hamutuk also learned that some perpetrators of minor crimes testified because they incorrectly believed that if they did not, the police would come to their houses and arrest them. Many people are confused and do not realize that the court system does not have the capacity to prosecute these crimes even if no CRP is reached.

There are concerns in this division that there are not enough staff members in CRP, and that the workload in the districts is very high. The staff from the CRP division complain that often they do not receive enough logistical support. For example, the staff in the districts have to walk to different villages, without motor transportation. We have also learned that the CRP process in Baucau has had many problems in part because CRP staff there are not working as a team.

This division of CAVR investigates human rights violations that occurred between 1974 and 1999, and will write a report on these violations and the factors that contributed to them. In this respect, CAVR not only looks into human rights violations on a case-by-case basis, but also examines whether these violations were part of a systematic pattern. For this reason, alleged cases of war crimes and crimes against humanity are part of the investigative functions of CAVR.

The Statement-Taking Unit of this division interviews victims and witnesses, and plans to collect up to 8000 statements. They have already taken approximately 5,900 in 51 of East Timor’s 65 subdistricts.

Each district has four statement-takers, two men and two women. Each staff member is provided with a statement form and a tape recorder. They also write a narrative of the story that they listen to. The Public Relations Unit disseminates information about the role of CAVR and identifies who will be asked to make a statement. Statement giving is voluntary.

The Truth-Seeking Division also includes the research unit and the Data Processing Unit, which is further divided into two teams: statement readers who read and assign code numbers to statements, and data entry staff who enter the information into the database. The research is divided into ten investigative themes: forced displacement and famine, massacres, killings and disappearance, political imprisonment and torture, women and conflict, children and conflict, party conflict, TNI, Fretilin/Falintil, and international actors.

Of the 5,900 statements collected so far, more than 2,000 have been entered into the database. Database delays and other problems have made it difficult for the research part of the Truth-Seeking Division to use the statements for their analyses of trends and patterns; similar problems have arisen in truth commissions all over the world.

Through the truth-seeking division, CAVR conducts research about cases related to mass murder, genocide and other politically motivated killing between 1974 and 1999. This research also includes international actors, both civilian and military, that were involved both directly and indirectly in East Timor, although most statements will not include details on international involvement. To gather information on international actors, the CAVR research team has asked foreign governments for information and documents, but it has been slow in coming. This research process is continuing, and the data is still being kept confidential. The research is being done by researchers from academic institutions and from NGO’s.

One of the goals of the research is to accurately estimate the number of people who were killed during the 24 years of Indonesian occupation. This is being done with a “Retrospective Mortality Survey” that combines information from cemetery surveys, interviews, demographic data and other sources. Questions have been raised about the accuracy of the raw data, and about the resources that will be required to carry out such a difficult task properly, given other needs. Some people believe that counting the number of people killed is not as important as identifying the strategies, policies, killers and masterminds that took their lives.

CAVR has held public hearings in East Timor on “Political Imprisonment”, “Women in Conflict,” and “Famine and Forced Displacement.” Victims and experts presented testimonies, which were widely covered on television and other media, relating facts and experiences to help the broader public understand the reality faced by the people of East Timor during the Indonesian occupation. Over the next year, additional hearings are planned on “Political Conflict 1974-76”, “International Actors”, “Massacres” and perhaps other topics.

The CAVR was considering holding public hearings overseas (in the United States, Australia and perhaps Indonesia) to provide an opportunity for policy-makers and experts from the U.N. and these countries to give testimony about their and their governments’ role in human rights violations in East Timor between 1974 and 1999. Unfortunately, this project has been essentially cancelled, ostensibly due to lack of human and financial resources. But some worry that CAVR’s priorities are influenced by political considerations, perhaps including reluctance by CAVR and others to embarrass international supporters of Indonesia’s occupation.

Concerns have also been raised about the overall results of the truth-seeking research, and whether the final report might be edited to meet domestic or international political concerns. Many of the international donors and agencies who are making CAVR’s work possible were complicit in Indonesia’s occupation of East Timor, either actively or passively, and they may not want the full story told. Although some perpetrators, especially the Indonesian military, will reject the report as based on research solely from pro-independence researchers and witnesses, it is still important to try to be as objective and accurate as possible. This research is costing a lot of money, and should not just end up in a file cabinet or wastebasket, without serving victims’ need for justice and recognition.

CAVR invited the Inspector General of RDTL to perform an audit and so far this has been done twice, and has found that in general things were in order, although there were a few technical problems. In order to avoid technical problems in the future, CAVR has begun to list all their large and small assets. Apart from that, the finance division recently decided to decrease spending by limiting phone cards and vehicle refueling. In addition, two CAVR staff in Baucau had their contracts terminated after $1,145 disappeared.

Another problem in this division is that local staff do not have enough experience in financial administration. Recently, skills transfer from international staff to local staff has begun to improve.

Planned expenditures during the 21/2-year life of CAVR | |

| Salaries | $1,685,669 |

| Pre-Commission Costs | $31,770 |

| Office & Program | $836,703 |

| Property Expenses | $80,000 |

| Vehicle Expenses | $214,000 |

| Training & Public Education | |

| Research | $102,800 |

| Buildings (mostly renovating prison) | $426,000 |

| Vehicles | $302,000 |

| Furniture & Equipment | $238,000 |

| Victim Support | $166,400 |

| Final Report | $96,300 |

| Contingency | $120,900 |

| Total expenses | $4,550,672 |

| Source: CAVR | |

Funds already received | |

| Donor | Amount |

| Australia | $160,711 |

| Britain (4 grants) | $516,347 |

| Canada | $190,076 |

| European Comm. (via UNHCR) | $316,982 |

| Finland | |

| Germany (2 grants) | $218,956 |

| Hivos | $34,249 |

| Ireland (3 grants) | $311,829 |

| Japan (2 grants) | $764,681 |

| New Zealand | $292,091 |

| Norway | $252,838 |

| UNDP-Sweden | $191,250 |

| USAID | $5,191 |

| USAID (in kind) | $117,547 |

| U.S. Institute for Peace (2 grants) | $40,000 |

| World Bank Community Empowerment Project | $80,000 |

| Total receipts | $3,512,743 |

| Source: CAVR | |

Funds promised but not yet received | |

| Donor | Amount |

| Ireland | $136,300 |

| Japan | $235,000 |

| UNDP-Sweden | $12,009 |

| USAID | $316,982 |

| USAID (in kind) | |

| World Bank-CEP | $86,400 |

| TOTAL | $669,665 |

| Source: CAVR | |

The Victim Support Division facilitates activities to contribute to the rehabilitation of victims of human rights violations. It organizes village level support to those who give statements and participate in community reconciliation, as well as sub-district victims’ hearings, community-based discussions on the impact of violence, and healing workshops for some survivors of serious human rights abuses. The Victim Support Division also tries to link survivors with urgent needs with organizations which can provide services to them, including to CEP’s vulnerable person’s program. A working group which involves Fokupers, Carmelite Nuns, HAK Association is involved in the implementation of this referral program for victims with urgent needs.

In order to ease the difficulties experienced by victims, CAVR received approximately $166,000 from the Community Empowerment Project (CEP), to be given to victims. According to information obtained by La’o Hamutuk

At the end of its mandate, CAVR will develop recommendations around reparations and rehabilitation of victims.

Program Support Division (formerly External/Public Relations Division)

This division has three units: Media and Public Information, Public Relations, and Institutional Development. The first unit carries out information dissemination in the community, including activities like:

The Public Relations Unit develops relationships with groups in East Timorese society, including NGOs, political parties, churches, youth and women’s organizations. There is one public relations staff in each district to socialize CAVR’s work, and help identify victims and perpetrators who will be asked to give statements, participate in public hearings, or take part in community reconciliation processes.

The Institutional Development Unit identifies problems and needs within CAVR. It focuses on capacity building, holds trainings, and helps evaluate staff capacity and quality of work.

The CAVR proposal circulated for public consultation in late 2000 said that “all permanent staff will be nationals. A few international consultants are likely to be contracted to assist the commission for relatively short periods, especially on technical matters.” At present, the commission has fifteen international staff, including eleven paid by other organizations, and several other international consultants contracted for one or two months. The international staff hired directly by CAVR include two translators, one researcher and one advisor.

Unlike most international staff and advisors working in East Timor, many of the internationals working in CAVR have long supported East Timor’s struggle for independence as volunteer activists in the international solidarity movement. Their knowledge of East Timor’s history, empathy for the East Timorese people, and skills in Tetum and Bahasa Indonesia are far better than most internationals here. Given this context, we were surprised to learn that CAVR experiences many of the same problems between locals and internationals that are pervasive in this new country. This shows just how difficult it is to build an equitable working environment when people have widely varying pay scales, levels of experience, expectations, and conditions of work.

The majority of the international staff who are currently working for CAVR are paid by voluntary contributions through UNDP for the 200 development “posts” identified by UNDP for government administration and capacity building of civil servants. As such, they do not submit to the personnel policies and work rules of CAVR, causing some resentment among their East Timorese colleagues, including commissioners. Several of the commissioners did not know about new international staff working at CAVR, even though a recently-formed recruitment team for international staff includes two national commissioners. Even after this team was established, many feel that international advisors already at CAVR have the main role in deciding about new international staff, because they already know the people who apply for the jobs.

The Program Manager is an international advisor under contract with UNDP. As a result, many CAVR staff do not understand the functions of the international advisors; are they decision-makers or advisors to East Timorese staff and commissioners?

La’o Hamutuk learned that the evaluation process for international advisors contracted by UNDP is questionable, with evaluation forms sometimes being seen by the people being evaluated, which makes it difficult to give an independent and transparent evaluation.

Many of the East Timorese CAVR staff contacted for this article felt that some of the international advisors make decisions without discussing them first with the relevant division coordinator, who is a national staff member. As a result, there appears to be widespread feeling among CAVR national staff that the institution is dominated by international staff. Rather than acting as the mentors they are hired to be under UNDP regulations, some international staff perform line functions. On the other hand, some national staff feel that the advisors should be doing the difficult line-work, considering that they receive very large salaries from international agencies.

It is clear that better cooperation and communication is needed between the national staff and the advisors to identify how the advisors can truly help and prepare the national staff to work on their own. This process of communication is important because many national staff still feel like their work is being interfered with. Although international staff language skills are better than in other agencies, national staff sometimes complain about difficulties in communicating with international advisors although they recognize that the fluent English of many international staff is very helpful in relating to donors and international agencies.

The role of international staff is further confused by the temporary nature of CAVR; both international and local staff will lose their jobs when CAVR ends in 2004. Although on-the-job training will benefit local staff and East Timor as a whole, it may not add much to CAVR’s efficiency during its limited mandate.

Some also say that the national staff do not possess adequate capacity or are not pro-active enough in gaining skills that international staff already have, although others feel that the hiring process for national staff, especially executives, could have chosen people with more experience.

After La’o Hamutuk had begun interviewing people at CAVR, CAVR management apparently told CAVR national staff below the level of heads of division not to speak with La’o Hamutuk researchers. Although we understand the need for CAVR staff to focus on their primary work, this directive raises questions about transparency and openness. We hope it is not a sign of institutional defensiveness that could make it more difficult for CAVR to serve its primary constituency — East Timor’s people, especially victims of human rights violations — effectively, using all available information and human resources, both inside and outside CAVR.

When CAVR publishes its final report a year from now, it will have taken on many difficult problems, assimilating diverse and sometimes subjective information, working in multiple languages, and navigating between real and potential political pressures. We hope the report will be well-researched and well-accepted, and that it will shed new light not only on what was done to people in East Timor between 1974 and 1999, but how it was done, why, and by whom. We also look forward to CAVR’s recommendations for continuing work in justice, reconciliation, reparations and truth-seeking, as well as follow-up actions and policies. We encourage CAVR’s report-writers to think boldly and broadly, and to discuss potential recommendations with a broad range of people in East Timor. In the long run, this can be the most valuable and important result of CAVR’s work.

CAVR has and will continue to perform valuable services in acknowledging victims’ experiences, implementing restorative justice at the community level, and uncovering and publicizing information about human rights violations committed in East Timor since 1974. However, there are questions about whether it is truly directed by East Timorese people, appropriate to the needs of this nation and serving the priorities of the East Timorese population. And how much has it cost this country in lost opportunities to hold major perpetrators accountable for their crimes?

According to Patrick Burgess, former UNTAET Director for Human Rights and currently legal advisor for the CAVR national commissioners, “we must seek justice for the past human rights violations in East Timor wherever it is possible. There are a number of avenues for seeking this justice. They include the possibility of an international tribunal, the ad hoc Tribunal in Jakarta, the Serious Crimes Process and the CAVR. In my personal opinion we need to pursue every possible avenue for attaining the justice we seek.” Patrick points out that there are political difficulties with the establishment of an international tribunal, and that the ad hoc Tribunal in Indonesia is a sham. Serious Crimes has had problems and is now more effective, but has no access to major perpetrators in Indonesia. On the other hand, he sees the Community Reconciliation process of CAVR as relatively successful, although it only deals with less-serious perpetrators, whose victims also deserve a voice and an opportunity to restore their dignity. The truth-seeking part of CAVR’s work is investigating serious crimes as well as other human rights abuses, and Patrick expects that its final report will include recommendations about these violations and offences against international law, and the responsibility for these violations.

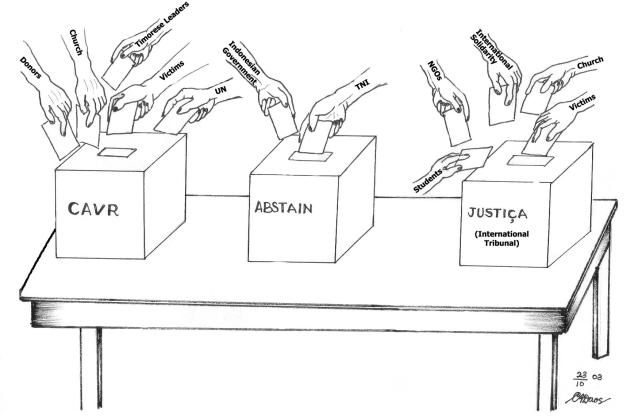

La’o Hamutuk believes that an international tribunal to try crimes against humanity committed in East Timor should still be established. (See Editorial, LH Bulletin Vol. 4, No. 2.) The question is, do the members of the United Nations have the will to initiate an international tribunal? An international tribunal is not the responsibility of East Timor alone, but also of the international community, particularly the United Nations, not least because crimes against humanity transgress universal human rights, and because crimes committed during the 1999 referendum period were in direct violation of an agreement Indonesia had signed with the United Nations.

In 2000, while CAVR was being proposed and discussed, there was much stronger support for an international tribunal than there is now, but the CAVR and the Indonesian ad hoc human rights court in Indonesia allowed the international community to delay. Politicians and diplomats claimed that these processes were, in some way, dealing with the pressing need for justice. Now, three years later, the possibilities for international justice are weaker, although most of the major perpetrators still enjoy impunity in Indonesia.

Many people feel that the CAVR’s minor-crimes reconciliation process is diverting attention from victims’ demand for justice for crimes against humanity. Although restorative justice involving minor perpetrators is worthwhile, it does not end impunity for those who committed and directed major crimes, many of whom are repeating this criminal behavior in Aceh, West Papua, and elsewhere in Indonesia.

We are concerned that the United Nations, foreign governments and East Timorese political leaders, have been and will use the CAVR as an excuse for not pushing for legal action against those that have committed serious crimes, even though serious crimes are outside the scope of the Commission. A new government, faced with budgetary concerns and other national and international pressures could be persuaded to downplay conventional justice, particularly due to limited resources and experience.

In its July 2001 report about justice, Amnesty International applauded CAVR’s authority to refer cases of serious crimes to the General Prosecutor. However, Amnesty “very much doubted the current capacity to be able to process these cases effectively and in an adequate time frame.” In this sense, there is a concern that CAVR is using political and financial resources that could have been allocated to the justice system, even though reducing the burden on the courts was one of the reasons for establishing the Commission. (see La’o Hamutuk Bulletin Vol. 2 No. 6-7

La’o Hamutuk hopes that CAVR’s final report will strongly support justice by providing new information and renewed pressure on the international community to fulfill its legal and moral obligation by holding perpetrators of serious crimes accountable, thereby providing some relief for thousands of victims.

La’o Hamutuk staff: Cassia Bechara, Simon Foster, Tomas (Ató) Freitas, Selma Hayati, Mericio (Akara) Juvinal, Yasinta Lujina, Inês Martins, Charles Scheiner, João Sarmento, Jesuina (Delly) Soares Cabral, Andrew de Sousa

Drawings for this Bulletin: Cipriano Daus

Translation for this Bulletin: Xylia Ingham

Executive board: Maria Domingas Alves, Sr. Maria Dias, Joseph Nevins, Nuno Rodrigues, Aderito de Jesus Soares

In the spirit of encouraging greater transparency,

Job Announcement

La’o Hamutuk is looking for a half-time East Timorese staff member to be responsible for finances and accounting. Qualifications: at least one year accounting experience, good English and computer skills. Interested applicants should bring CV, a letter explaining why you want to work with us, and two references to La’o Hamutuk’s office.

Application deadline 30 November 2003.

La'o Hamutuk, The East Timor Institute for Reconstruction Monitoring and Analysis

P.O. Box 340, Dili, East Timor (via Darwin, Australia)

Mobile: +(670)7234330; Land phone: +670-3325-013

Email: laohamutuk@easttimor.minihub.org; Web: http://www.laohamutuk.org